Inguinal Canal: Anatomy and Hernias

Inguinal Canal: Anatomy and Hernias

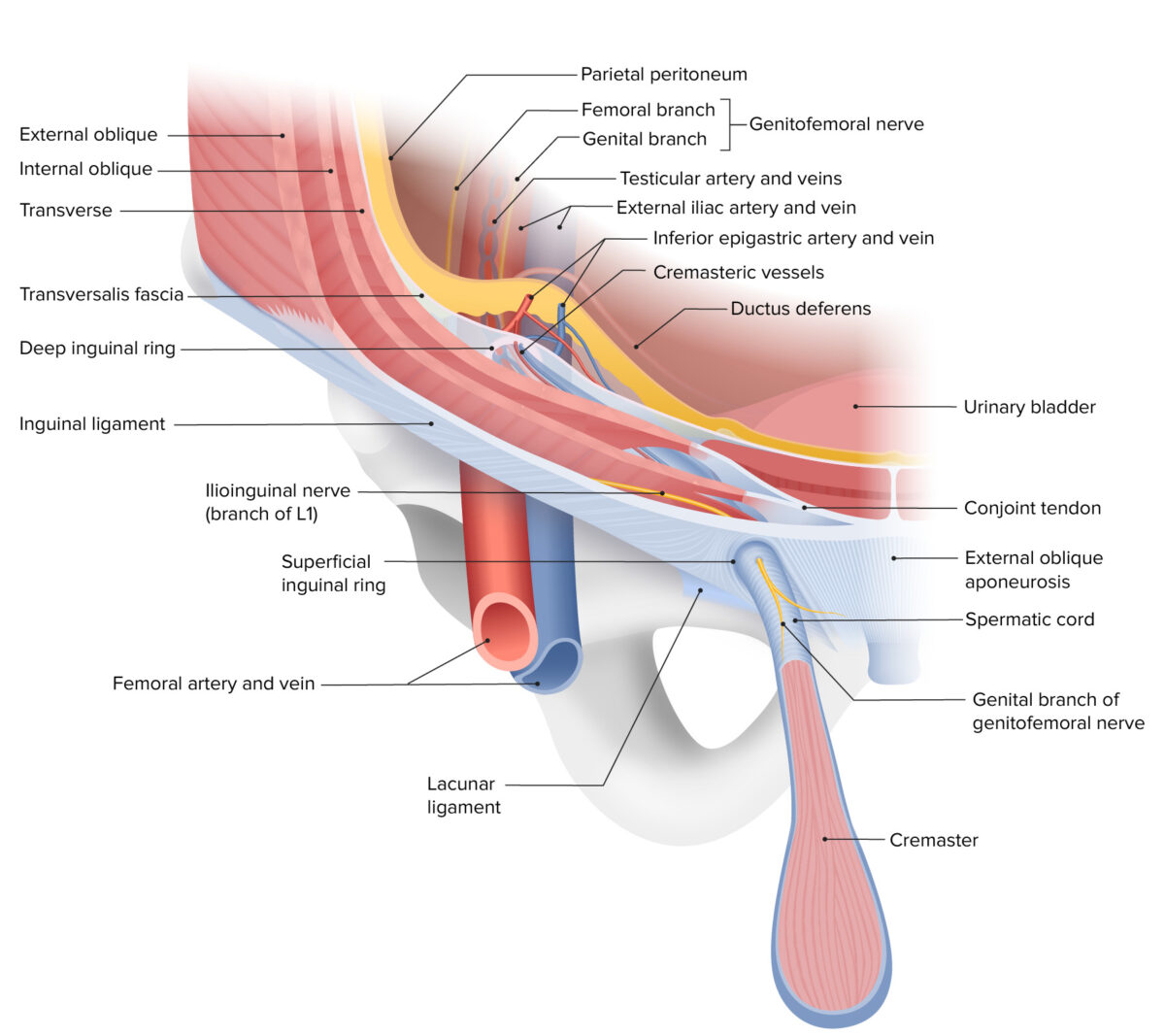

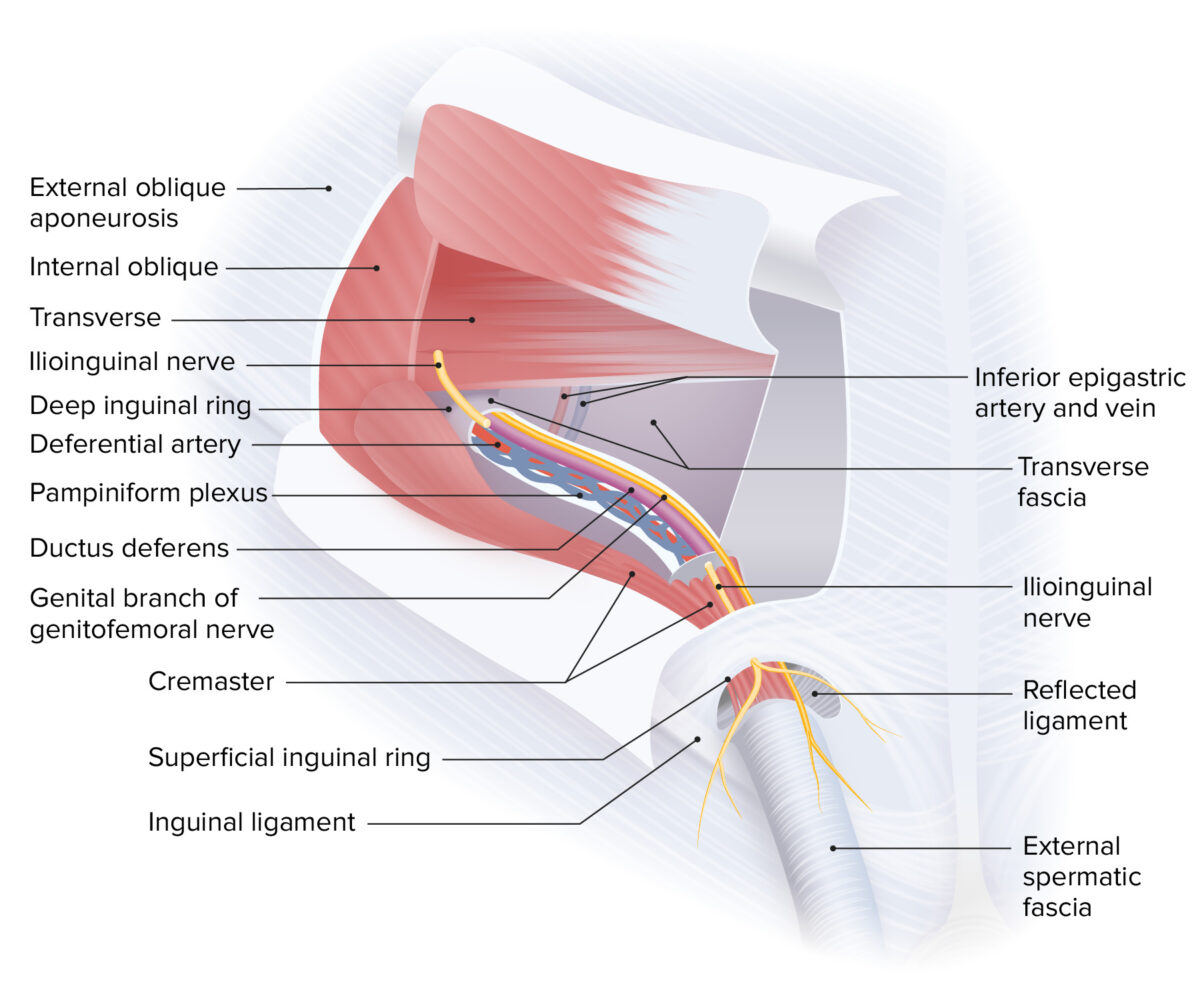

The inguinal region, or the groin, is located in the RLQ and LLQ of the anterior abdominal wall, bordered by the thigh inferiorly, the pubis medially, and the iliac crest superolaterally. The inguinal canal is a tubular structure that runs in a straight line from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle. The canal contains the spermatic cord in men and the round ligament in women. An inguinal hernia occurs when tissue or an organ (such as a portion of the intestine) protrudes through in the abdominal wall and into the inguinal canal. Inguinal hernias are the most common type of hernia, and may be classified as indirect (tissue protrudes through the deep inguinal ring) or direct (tissue protrudes through the posterior wall of the inguinal canal). A hernia may cause pain or discomfort, and there is a risk of bowel obstruction due to bowel incarceration with possible strangulation and infarction. Surgery is indicated for inguinal hernias which are high-risk or cause significant pain.

Overview

- The , or the , is located in the RLQ and LLQ of the anterior .

- Boundaries:

- inferiorly

- Pubic tubercle medially

- laterally

- The inguinal canal runs in a straight line from the to the pubic tubercle.

- Contents of inguinal canal:

- Men:

- (with genitofemoral nerve)

- Ilioinguinal nerve

- Women:

- Genitofemoral nerve

- Ilioinguinal nerve

- Men:

- Hesselbach triangle:

- A triangle of the

- Located medial to the epigastric vessels

- Site of direct inguinal hernias

Embryologic Development

Formation of the inguinal canal

- Independent of testicular descent, in the 12th week of gestation, the anterior musculature and form an evagination on each side of the midline known as the processus vaginalis.

- The processus vaginalis, in combination with the muscle and of the anterior , forms the inguinal canal.

- In women, the ovum descends into the , and the of the travels through the inguinal canal to the .

Male inguinal canal development

- The originally reside in the posterior aspect of the abdominal cavity.

- Between 28 and 33 weeks' gestation, the pass through the and into the .

- The , of mesenchymal tissue that terminates in the on the caudal pole of the , assists the in their migration.

- Failed testicular descent results in .

- Descent of the creates a weakness in the in the region of the inguinal canal, making men particularly susceptible to formation.

- The connection between the processus vaginalis and the will obliterate at birth, but a serous sac will remain around the , known as the testis.

- contributions:

- Transversalis forms the internal spermatic .

- muscle forms the cremasteric and muscle.

- muscle forms the external spermatic .

Inguinal Canal Anatomy

Anterior

- The anterior is composed of several muscles:

- The inner transversalis continues into the inguinal canal, forming the internal spermatic .

Course of the inguinal canal

- Approximately 4 cm long from to pubic tubercle (superolaterally to inferomedially)

- Deep inguinal ring: an evagination of the transversalis (surrounding the as the internal spermatic )

- Superficial inguinal ring: a in the aponeurosis of the muscle

Boundaries of the inguinal canal

The boundaries of the inguinal canal vary throughout its course.

- At the level of the deep ring:

- Anterior wall:

- muscle

- muscle

- Posterior wall: transversalis

- Roof: transversalis

- Floor:

- Anterior wall:

- At the middle of the inguinal canal:

- Anterior wall: aponeurosis

- Posterior wall: transversalis

- Roof: arching fibers of the muscle and

- Floor:

- At the level of the superficial ring:

- Anterior wall: aponeurosis

- Posterior wall: conjoint tendon

- Roof: medial crus of muscle

- Floor: lacunar ligament

Borders of the Hesselbach triangle

- Refers to a triangle of the anterior

- Boundaries:

- Medial: lateral margin of the (linea semilunaris)

- Superolateral: inferior epigastric vessels

- Inferior: inguinal and pectineal ligament

- Direct hernias occur within the triangle, and indirect hernias occur lateral to the triangle.

Epidemiology and Etiology of Inguinal Hernias

Epidemiology

Risk factors

- History of or previous repair

- Male

- Older age

- Chronic obstructive ()

- Chronic

- Weight lifting

Etiology

- :

- Due to abnormal development

- Failed closure of the processus vaginalis

- Acquired:

- Develop later in life due to progressive weakness of previously normal tissues

- Conditions with increased intraabdominal pressure, such as strenuous physical activity, coughing, or

- Sometimes due to injury or abdominal surgery

- All direct hernias are acquired, while indirect ones may be or acquired.

Classification and Clinical Presentation

Classification

- Indirect hernias:

- Lateral to the inferior epigastric blood vessels and the Hesselbach triangle

- Contents pass through the deep inguinal ring, traverse the entire trajectory of the inguinal canal, and exit the canal through the superficial inguinal ring.

- Contents are encased by the coverings of the .

- Direct hernias:

- Medial to the inferior epigastric blood vessels and within the Hesselbach triangle

- Contents protrude directly through the posterior wall of the inguinal canal and through the superficial inguinal ring, encased only by the external spermatic .

- Pantaloon : inguinal with both direct and indirect components

- Amyand : The is found within the sac.

Clinical presentation

- Mild inguinal or discomfort

- Visible bulge in the area, which increases upon standing or during physical activities that increase intraabdominal pressure (coughing, , weight lifting) and reduces upon lying down.

- May be associated with a communicating

- may be noted over the if there is strangulation and tissue death.

Complications

- Incarceration:

- Inability of the contents of the to return to their original cavity

- Presents with severe and a non-reducible bulge

- If the intestines are incarcerated, symptoms of develop.

- Strangulation:

- Contents of the must first become incarcerated.

- Blood supply to the incarcerated organs is compromised, which causes and resultant tissue death.

Diagnosis and Management

Diagnosis

- Medical history and physical exam

- of the inguinal canal:

- With the patient standing, palpate from the scrotal toward the superficial inguinal ring.

- Ask the patient to cough ().

- Bulging can be felt at the fingertip.

- Imaging:

- Used for confirmation in uncertain cases and occasionally surgical planning

- Ultrasound :

- Best initial imaging study in without physical evidence of a

- The diagnostic finding is an increased diameter of the inguinal canal (normally < 13 mm at the deep inguinal ring).

- CT scans: particularly useful to distinguish between different subtypes of inguinal hernias

- MRI:

- Best imaging modality to differentiate between inguinal and femoral hernias with a greater than 95%

- Due to the cost and limited availability of MRIs, CT scans are still more frequently used.

Management

- Surgical repair:

- Complicated hernias

- Uncomplicated hernias with moderate symptoms

- Selectively for uncomplicated hernias with mild or high risk of incarceration

- Specifics of surgical repair techniques can be found in abdominal hernias.

- Surgical techniques:

- Reinforcing the posterior wall of the inguinal canal with synthetic mesh

- Reduction in the diameters of the inguinal rings